BY Noah Martin

Noah Martin is a first year MAIR student studying Development, Climate, and Sustainability, focusing on Europe and Eurasia. He aspires to use his SAIS experience to promote equitable access to goods and services in developing countries, especially technology that can help change lives.

INTRODUCTION

The “utility death spiral” occurs when utility customers leverage distributed electricity supplies, especially home-owned solar panels, and thus pay a lower energy bill. When enough users make the switch, electricity suppliers must raise their rates to cover maintenance costs. This causes more customers to switch away due to these higher prices, a vicious cycle that power generators, transmitters, and distributors (often vertically integrated) fear will make them insolvent. So that electricity users are not excluded from the transition to solar, and relatedly not made to pay the price for others’ shift to renewable energy, the promotion of access to solar panels must be rethought. Decentralized solar panels have the potential to democratize solar energy, providing cheap power access and enabling customers to sell energy back to the grid. However, government intervention in some areas has not been sufficient to protect utility companies from new, smaller-scale energy trends.

This phenomenon has been studied thoroughly in the developed world, but less so in developing countries. This case study examines the dynamics of the “utility death spiral” in Maharashtra, the second most populous Indian state and the third largest in land area [1]. The state is home to Mumbai and Pune, India’s largest and ninth largest cities, but also a significant agrarian population, making it a complicated electricity market. There is potential for increased solar energy capacity in the state, presenting not only an enormous opportunity to include all consumers in the green transition, but also introducing an inevitable threat to utility companies.

BACKGROUND

India’s utility model is federated, meaning electricity is managed on a state-by-state basis. It is the third largest electricity producer in the world (1,844 TWh in 2022), and given the country produces three-quarters of its electricity from coal, it is one of the largest CO2 emitters [2]. India is increasingly looking toward renewables to meet consumer demand, and proved this stance by announcing it would not build new coal plants from scratch for the next five years [3].

Maharashtra’s energy supply was managed by MSEB (Maharashtra State Electricity Board) for many years, but the Energy Act of 2003 split the company into four pieces . MSEDCL (Maharashtra State Electricity Distribution Company Ltd.) manages distribution, MSETCL (Maharashtra State Electricity Transmission Company Ltd.) manages transmission, MSPGCL (Maharashtra State Power Generation Company Ltd.) manages generation (coal, natural gas, wind, and hydro), and MSEB Holding Company Ltd manages the financial side, holding a 100% stake in the service providers. MERC (Maharashtra Electricity Regulatory Commission) was also founded in 1999 as an independent regulator of utilities, ensuring their efficiency and consumer fairness. This breakup of the utility company was meant to increase competition, improve utility company efficiency, provide reliable and affordable electricity to consumers, and increase investment in renewable energy [4]. Maharashtra is also home to independent power companies that represent the primary power supply of Mumbai, including Brihanmumbai Electricity Supply & Transport, Tata Power, and Adani Electricity Mumbai [5]. These companies share the urban market partly due to Maharashtra’s energy prices, which are the highest in India [6].

Elavarasan, Madurai, et al. “A Holistic Review of the Present and Future Drivers of the Renewable Energy Mix in Maharashtra, State of India.” [7]

ANALYSIS

Maharashtra is an exemplary location for solar implementation due to its geography, which has increased speculation of a looming utility death spiral. The state experiences 250-300 sunny days per year, rendering solar power a highly available resource. The advent of net metering policies has enabled panel owners to sell energy back to the grid, which helps alleviate the state’s high electricity tariffs. These conditions have helped make Maharashtra India’s largest rooftop solar state in terms of capacity (Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, and Gujarat comprise 30% of all distributed solar deployment) [8].

On the agricultural side, there are several studies on the potential for decentralized solar-powered irrigation pumps. While grid-based energy is seen as advantageous because it is constantly available, it is not always fully reliable. Net-metering allows farmers to leverage both grid and solar energy sources and sell their extra energy back to the grid. The state of Maharashtra heavily subsidizes solar PV pumps, with most farmers only having to pay 5–10% of the cost, resulting in extra income of $45 and $145 annually from net metering with small and large pumps, respectively. In a future scenario without subsidies, even with very high costs of solar pump implementation, these costs are expected to have economies of scale [9]. Maharashtra is also home to numerous urban centers with the potential for decentralized solar energy. As of 2015, only .1% of Mumbai’s energy came from decentralized solar. One study suggests that using the highest efficiency solar panels on commercial markets, Mumbai could produce anywhere from 47.7%–94.1% of its peak morning demand [10].

It seems that the future of decentralized solar in India is bright. While centralized solar is less expensive than most decentralized projects (INR 3.32/kWh vs INR 4.07/kWh), power losses during grid transmission raise the costs of centralized solar projects to around INR 4.05/kWh. With roughly equal costs of centralized and decentralized solar energy, the latter may also present advantages with smaller entities, as decentralized power has fewer barriers to entry and does not require large swaths of land [11].

The utility providers in Maharashtra seem aware of a potential utility death spiral, and their fears are based in reality. Prayas, a Pune-based NGO focused on energy, attempted to hold MSEDCL accountable after the distribution company issued their Multi-Year Tariff petition back in 2015. They remark that MSEDCL’s proposed tariff increases will cause “big consumers [to] avail alternative lower cost solutions,” of which solar is a good fit, and that the utility “must start taking actions that will arrest this downward spiral.” [12]

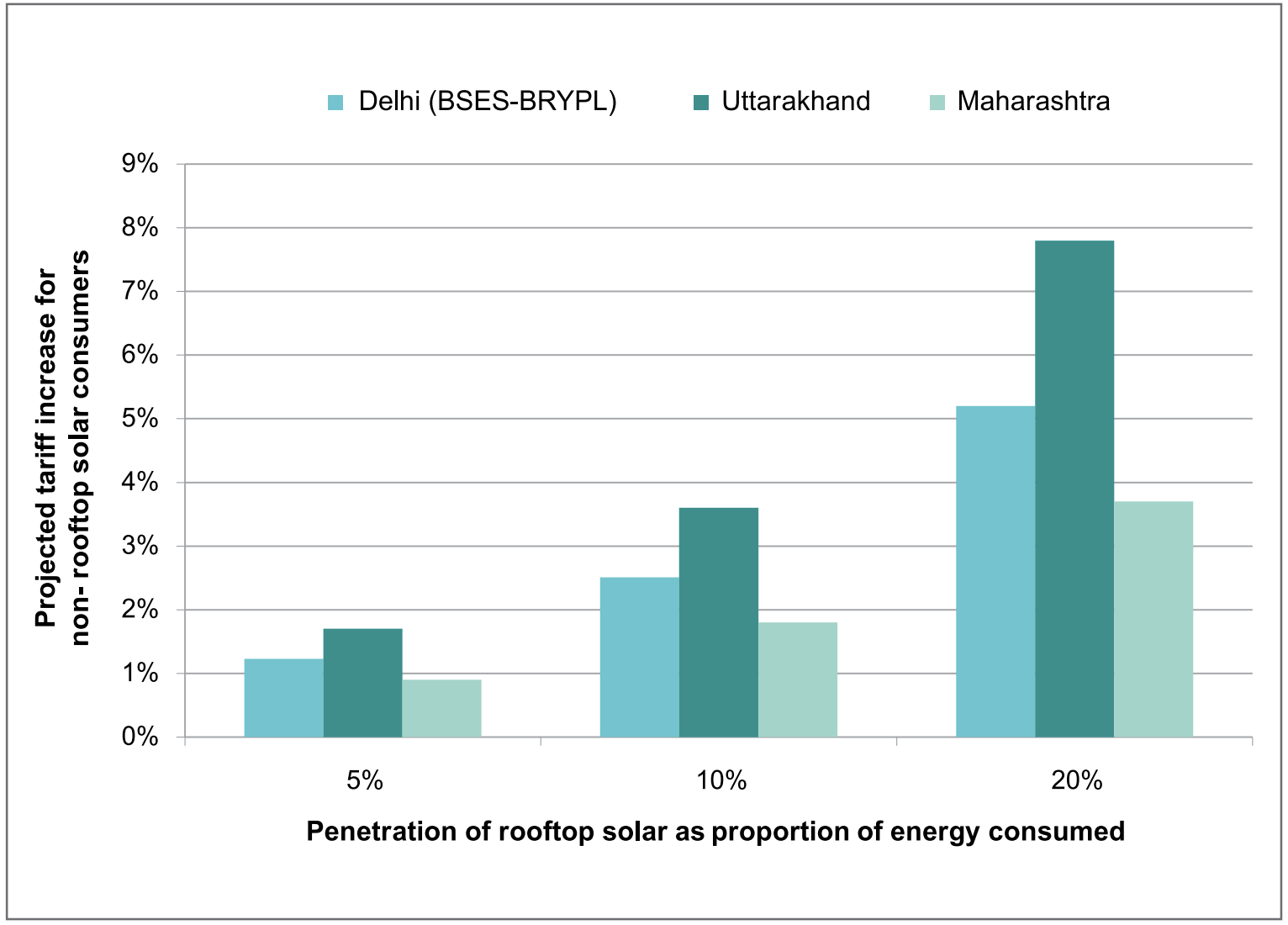

Despite these exhibited fears of a utility death spiral and immense solar potential in Maharashtra, the chances of decentralized solar adoption causing any immediate detriment to utility companies are low. In general, India is still a growing electricity market, even in more developed states like Maharashtra; from 2021 to 2022, energy consumption in the state grew from 126,423 GWh to 142,088 GWh [13]. Even with the growth of rooftop solar, it is likely that MSEDCL will continue to acquire enough new customers annually to offset this decline. A study by the Nand & Jeet Khemka Foundation projects that for Maharashtra, 20% rooftop solar penetration would only result in a 3.75% increase in energy tariffs, which means that in 2022, tariff increases would have been less than 2% [14].

Source: The Climate Group. Unleashing Private Investment in Rooftop Solar in India [15].

Increased adoption of distributed solar over time will decrease distribution companies’ (“discoms”) fixed rate of return on capital, a wrench in their long-term business model and ability to pay off obligations, like maintenance costs. However, it may provide benefits to the system as well. Discoms can approach distributed solar energy by buying power rights from third parties that lease rooftops and cover expensive panel installation costs, which consumers often cannot afford. By helping to finance the purchase of the solar panels, the discom can charge a lower tariff than before for small consumer energy usage but at a higher margin without costly wire losses and heavy strain on distribution networks during peak summer days [16].

Utility companies are not rolling over to the adjustments that distributed solar will require them to make. Tata Power, one of the Mumbai urban utility providers (as well as a global conglomerate), produces solar panels in-house and has engaged in projects to increase distributed solar penetration. In 2017, it installed a solar rooftop at a Mumbai cricket stadium, the largest solar rooftop project at the time, reducing the power costs by 25% [17]. Earlier this year, it even installed a fully off-grid system at a residential community as a proof of concept for its panels [18]. Local Mumbai utility company Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation is slightly further behind, but installed their first panels on their office rooftops earlier this year.

MSEDCL is stepping into the space as well. For a long time, it had been resistant to the changes, fearing the death spiral. In 2020, it nearly doubled energy tariffs for rooftop solar through net metering. Instead of attempting to leverage these trends like Tata Power has, it has combated them, justifying these measures with their fixed costs [19]. More recently, however, it has moved more toward distributed solar; in April of 2023, it invited companies to bid on a decentralized solar project to procure 225 MW of power per year [20]. This project notwithstanding, as long as the discom can regulate energy prices, it will not allow net metering-attached distributed solar tariffs to fall below what it perceives as too low to cover their fixed maintenance costs.

Ultimately, the utility sector of Maharashtra has far bigger problems to address than the utility death spiral, which is, at worst, a medium to long-run concern. MSEDCL has been facing mounting losses (over 20.73%) despite loan repayment assistance from the UDAY scheme (a plan to assist financially ailing Indian state discoms) [21]. This is in large part due to poor collection from agricultural consumers and misappropriation of funds by executives, a pattern which is uniform across many Indian states. If MSEDCL cannot fix its financial management, it will be in danger of missing the boat on the solar revolution, as it will not be able to afford the high entry costs of capital in the solar space.

CONCLUSION

Maharashtra and its largest utility companies are not in immediate danger of facing a “utility death spiral.” A consistently growing customer base for conventional grid energy ensures only a high level of solar penetration would necessitate an increase in electricity tariffs. Despite this, MSEDCL has attempted to place barriers to entry on distributed solar generation over the past decade, increasing energy tariffs for those selling back to the grid to ensure they can continue to cover their fixed expenses. Simultaneously, the discom recognizes that they need to begin their solar project investment both in distributed and centralized. As Maharashtra is the state with the highest energy prices and geography amenable to solar energy, there is no doubt that all discoms in Maharashtra will need to adjust their models to protect themselves from becoming victims of growing distributed solar market penetration.

There is little empirical scholarship on the financial impact of distributed solar on utility companies in Maharashtra. It is expected that no utility company would disclose the impact of these dynamics, but also, few researchers have created models or projections that shed light on the subject. More studies and projections are required to gather more accurate data on the challenges caused by this new electricity trend. The more understood the market dynamics of distributed solar energy are, the better governments can promote legislation that enhances the ability of everyday citizens to participate in the distributed solar market while still protecting utility companies from further financial issues created by decentralized renewable energy adoption.

This research illuminates the high potential for solar energy in Maharashtra and demonstrates that through proactive policies and smart business strategies, the growth of distributed solar should be embraced rather than feared. By rethinking existing paradigms for tariff structures, renewable energy subsidies, and revenue streams, the distributed energy spiral can be one of renewed life, and integrate more consumers in the green-energy transition.

References:

[1] Elavarasan, Madurai, et al. “A Holistic Review of the Present and Future Drivers of the Renewable Energy Mix in Maharashtra, State of India.” Sustainability 12, no. 16 (January 2020): 6596. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166596

[2] “Climate Change Performance Index.” Accessed September 21, 2023. https://pib.gov.in/pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1884764

[3] AP News. “India Pauses Plans to Add New Coal Plants for Five Years, Bets on Renewables, Batteries,” June 1, 2023. https://apnews.com/article/india-coal-pause-plan-climate-renewables-68b75402af663e4553434bc672fc9cda

[4] Ministry of Law and Justice. “The Electricity Act, 2003 with Amendments – MERC.” Accessed September 21, 2023. https://merc.gov.in/the-electricity-act-2003/

[5] Dixit, Kalpana. “Paradoxes of Distribution Reforms in Maharashtra.” In Mapping Power: The Political Economy of Electricity in India’s States, edited by Navroz K. Dubash, Sunila S. Kale, and Ranjit Bharvirkar, 0. Oxford University Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199487820.003.0009

[6] Gokarn, Kanak, Nikhil Tyagi, and Rahul Tongia. “A Granular Comparison of International Electricity Prices and Implications for India - CSEP,” June 10, 2022. https://csep.org/working-paper/a-granular-comparison-of-international-electricity-prices-and-implications-for-india/

[7] Elavarasan, Madurai, et al. “A Holistic Review of the Present and Future Drivers of the Renewable Energy Mix in Maharashtra, State of India.” Sustainability 12, no. 16 (January 2020): 6596. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166596

[8] Sivaram, Varun, Gireesh Shrimali, and Dan Reicher. “Reach for the Sun: How India’s Audacious Solar Ambitions Could Make or Break Its Climate Commitments.” Stanford Law School. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://law.stanford.edu/publications/reach-for-the-sun-how-indias-audacious-solar-ambitions-could-make-or-break-its-climate-commitments/

[9] Jadhav, Priya Jayawant, Namita Sawant, and Athira Madhusudhana Panicker. “Technical Paradigms in Electricity Supply for Irrigation Pumps: Case of Maharashtra, India.” Energy for Sustainable Development 58 (October 1, 2020): 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2020.07.005

[10] Singh, Rhythm, and Rangan Banerjee. “Estimation of Rooftop Solar Photovoltaic Potential of a City.” Solar Energy 115 (May 1, 2015): 589–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2015.03.016

[11] Thapar, Sapan. “Centralized vs Decentralized Solar: A Comparison Study (India).” Renewable Energy 194 (July 1, 2022): 687–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2022.05.117

[12] Prayas Energy. “Prayas Comments on MSEDCL Petition for Multi Year Tariff (MYT) for FY 2013-14 to FY 2015-16,” April 17, 2015. https://energy.prayaspune.org/our-work/policy-regulatory-engagements/prayas-comments-on-msedcl-for-multi-year-tariff-myt-petition

[13] “Electricity Consumption: Utilities: Maharashtra | Economic Indicators | CEIC.” Accessed September 21, 2023. https://www.ceicdata.com/en/india/electricity-consumption-utilities/electricity-consumption-utilities-maharashtra

[14] The Climate Group. Unleashing Private Investment in Rooftop Solar in India.” Solar Business Hub | Resources. March, 2016. https://resources.solarbusinesshub.com/solar-industry-reports/item/unleashing-private-investment-in-rooftop-solar-in-india

[15] The Climate Group. Unleashing Private Investment in Rooftop Solar in India.” Solar Business Hub | Resources. March, 2016. https://resources.solarbusinesshub.com/solar-industry-reports/item/unleashing-private-investment-in-rooftop-solar-in-india

[16] “Rooftop Solar PV Projects – Saviour of Discoms or Vicious Cycle of Death? | LinkedIn.” Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/rooftop-solar-pv-projects-saviour-discoms-vicious-cycle-ranjan/

[17] “Tata Power Installed Solar Rooftop at Cricket Club of India, Mumbai.” Accessed September 24, 2023. https://www.tatapowersolar.com/press-release/tata-power-does-worlds-largest-solar-rooftop-installation-on-a-cricket-stadium-at-cricket-club-of-india-mumbai-through-its-solar-arm/

[18] Bureau, BL Mumbai. “In a First, Tata Power to Help Mumbai Housing Complex Go Green with Solar Energy.” BusinessLine, January 11, 2023. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/variety/run-on-the-sun-tata-power-helps-mumbai-housing-complex-go-green-with-solar-energy/article66365051.ece

[19] Mercomindia.com. “Maharashtra Proposes Grid Charges on Net Metering Rooftop Solar Systems Over 10 kW - Mercom India.” Accessed September 24, 2023. https://mercomindia.com/maharashtra-proposes-grid-charges-net-metering-rooftop-solar

[20] Mercomindia.com. “Maharashtra Floats Tender for 100 MW Distributed Solar Power Projects - Mercom India.” Accessed September 19, 2023. https://mercomindia.com/maharashtra-tender-100-mw-distributed-solar-projects

[21] Standard, Business. “Financial, Operational Turnaround of MSEDCL Not Achieved: CAG Report,” August 4, 2023. https://www.business-standard.com/companies/news/financial-operational-turnaround-of-msedcl-not-achieved-cag-report-123080400540_1.html

Photo Credit: Varun Sharma, Getty Images, Licensed with Canva Pro