BY SAHAR PRIANO

Sahar Priano is a first-year MA in International Economics and Political Economy student in Bologna. Along with her studies, Priano works as a researcher and sustainability consultant for a German-based firm.

The COVID-19 pandemic has crippled the world economy, exacerbated inequalities and strained governments’ resources in combating the worst wave of unemployment since the Great Depression. Yet, relief may be in sight: As vaccines roll out, the international dialogue is buzzing with hope for not only a recovery, but a new sustainable system that ensures economic security and addresses climate change.

So how do we practically reach that goal? The public sector will undoubtedly play a central role; however, government approaches to climate change are plagued with inefficient solutions for clean energy. To optimize public intervention, researchers at RMI are convinced that part of the answer lies with green banks. “Green” financial institutions channel public and private capital into low carbon, climate-resilient energy projects. Green banks are often publicly capitalized, yet as private institutions, they function as channels between the public and private sector. As active industry partners, green banks rectify information asymmetries and other market barriers implicit in public green energy deployment. For example, with £3 billion in initial capital, the United Kingdom’s green bank leveraged private funds that tripled the UK green infrastructure and established the largest offshore wind market in the world. As a new frontier for public-private partnerships, green banks may be an important tool for a resilient post-COVID recovery.

Furthermore, green banks mitigate risk, which crowds in more cautious investors. Green banks structure their own securitizations, provide credit guarantees, and bundle high risk-high reward R&D projects for more attractive private investment. In the last decade alone, green banks have gathered $24.5 billion and stimulated about twice that from the private sector. With often more local, dynamic information for investors, one RMI expert, Angela Whitney, stated, “green banks are market educators.”[1] Just their transaction history serves as valuable evidence to taxonomize green investments. By mitigating investment risk, green banks attract untapped domestic pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, and international capital through multilateral development banks.

Additionally, these financial institutions can nimbly respond to existing energy inequalities. Green banks accelerate investment prospects, which is good for employment. The International Renewable Energy Agency estimates that increasing investment in renewables could add up to 42 million jobs to the global market by 2050. Moreover, one green bank, Michigan Saves, observed barriers that low- and moderate-income residents faced in loan approvals for climate mitigation programs. Prioritizing those residents, Michigan Saves aggregated the projects and created a guaranteed loan program to ensure all segments of their community had access to clean energy retrofitting. While these households are supposed to be higher risk, Michigan Saves boasts a low 1.5% default rate. Applications for green banks go beyond crowding in more investment, they generate jobs and address underserved market segments, which will lead to a more just energy transition.

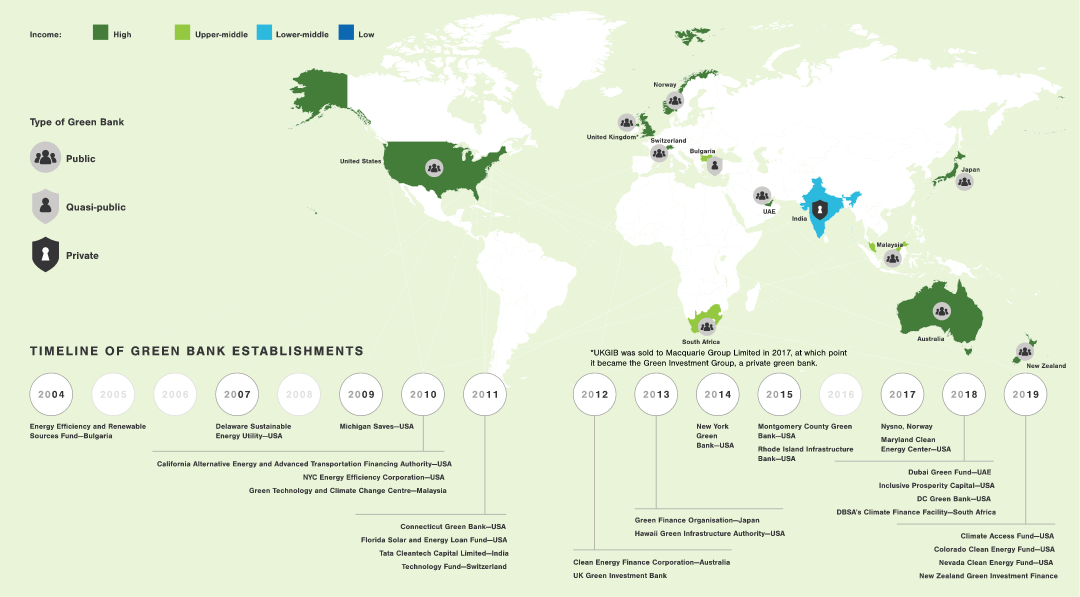

“Green banks are a clear institutional solution to turn ambition and policy into projects,” said Ms. Whitney.[2] The capacity to turn the commitments in the Paris Agreement into an attainable business model is generating interest. The Green Bank Network, an organization founded for bank collaboration already has ten members operational globally. Outside of this network, RMI reported 27 existing green banks and almost 30 jurisdictions in the process of establishing green banks.

Figure 1 - Development of Green Banks Globally (Source: RMI’s State of Green Bank 2020 Report)

Researchers at RMI are responding to this enthusiastic growth. The RMI report on green banks is a part of a larger green banking platform to support the development of green financial institutions in four ways:

Navigation and gap-filling: Addressing early barriers, finding the right stakeholders, and building political support;

Technical assistance: Playing a matchmaker role between consultants and banks;

Community of practice: Fostering collaboration to share lessons learned; and

Knowledge products: Compiling and ensuring the availability of relevant information.

Green banks further innovation and global competitiveness, and, therefore, carry important implications for a resilient recovery. In the short term, the advent of these financial institutions could counteract the decrease in private R&D investment, underwrite green projects, and support a just transition. In the long term, green banks could rectify incongruities between the private and public sectors towards a clean energy future.

Read the full 2020 RMI Report here.

[1] Whitney, A. (2021, Jan. 22). Interview on State of Green Banks 2020. Online.

[2] Ibid.

Other References

Buchner, B. et al., (2019). Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2019. Climate Policy Initiative. https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-landscape-of-climate- finance-2019/).

Grbusic, T. (2020). Green Banks for Economic Recovery and Climate Mitigation. Rocky Mountain Institute. https://rmi.org/green-banks-for-economic-recovery-and-climate-mitigation/

Nordhaus, W. (2004). Schumpeterian Profits in the American Economy: Theory and Measurement. No 10433, NBER Working Papers. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

OECD/IEA (2020) Energy Technology RD&D Budgets. International Energy Agency. Paris France.

Ogden, P., Podesta, J., and Deutch, J. (2008) A New Strategy to Spur Energy Innovation. Issues in Science and Technology 24(2). Winter, pp. 35-44.

Sivaram, V., and Norri, T. (2016). The Clean Energy Revolution, Foreign Affairs, V.95, 3, May/June 2016.

Thomas N. and Packard, J. (2020). “UK Ministers Plan ‘Green Investment Bank 2.0.’” Financial Times. https://www. ft.com/content/3350252b-6511-415d-9c19- e03351f646f9.

Whitney, A. (2021, Jan. 22). Interview on State of Green Banks 2020. Online.

Whitney, A., Grbusic, T., Meisel, J., Becerra Cid, A., Sims, D., and Bodnar, P. (2020). State of Green Banks 2020. Rocky Mountain Institute. https://rmi.org/insight/state-of- green-banks/

PHOTO CREDIT: Free use image from Canva Pro.