BY XINGYU PU

Xingyu Pu is a first year MAIR Student specializing in Development, Climate, and Sustainability. She once interned in the Green Finance Department of the Paulson Institute and has long been concerned about developing countries’s energy transition and sustainable financial development.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the intricacies of the Federal Reserve's interest rate policies, the complex energy crisis, and the ever-present specter of geopolitical conflict— one of the shared consequences of these challenges has been heightened global debt service pressures, which have had a particular impact on middle and low-income countries.

Among the various mechanisms available to countries seeking to restructure their debt, a distinctive approach intertwines debt relief with specific development objectives. This approach is embodied by the debt-for-nature swap (DNS) process, which has garnered widespread attention at the global level. At its core, the DNS embodies the notion of using debt relief to champion environmental conservation and sustainable development, and has the potential to simultaneously address global inequality and promote environmental justice.

This article outlines how the DNS acts as an innovative debt restructuring mechanism, not only serving to alleviate the debt burden of middle- and low-income countries, but also promoting environmental protection and sustainable development. It also explores the complexities and challenges facing the DNS process, which will require cooperation and coordination among creditor nations, debtor nations, and international organizations to overcome.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE DNS MECHANISM IN SOLVING THE CURRENT CRISIS

The rapid growth of external debt levels in emerging markets and developing economies in recent years, as highlighted by data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), has become a pressing international concern [1]. This surge in debt has not only burdened nations, but has also contributed to a widening gap in global economic inequality. The consequences of this debt crisis are multifaceted and affect both the global economy and local communities in impacted countries.

Under the current international debt structure, developing nations with high debt levels are often forced to allocate a significant portion of their budgets to debt servicing, diverting resources away from essential public services such as healthcare, education, and infrastructure development [2]. This, in turn, hampers social and economic progress, leaving local populations to bear the brunt of austerity measures.

The negative consequences of the debt crisis are further compounded by external factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic, Federal Reserve interest rate increases, energy crises, and geopolitical conflicts, all of which have hit vulnerable countries disproportionately hard. These global events have made it increasingly difficult for nations to manage their debts effectively, leading to a surge in sovereign debt defaults among emerging markets, as indicated by credit rating agencies like Fitch Ratings [3]. Resulting defaults not only damage countries' creditworthiness, but also have severe consequences for their citizens, who often face reduced access to credit, rising inflation, and diminished economic opportunities.

In this context, the debt-for-nature swap mechanism offers a glimmer of hope for debt-ridden nations and their populations. By providing a structured framework for debt relief and directing the saved funds into mutually agreed-upon development projects, this approach addresses the dual challenge of debt reduction and sustainable development [4]. This framework alleviates the burden of debt servicing, while empowering governments to invest in projects that benefit their citizens directly.

The DNS mechanism has the potential to significantly improve the lives of local populations, especially in climate-vulnerable developing nations [5]. These countries, as evidenced by data from the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) index and the IMF's "World Economic Outlook" report, often find themselves caught in a vicious cycle where high debt levels hinder their ability to invest in climate resilience and adaptation measures [6]. This vulnerability, coupled with higher borrowing costs, makes it challenging for these nations to respond effectively to the growing threat of climate change.

By enabling debt relief in exchange for nature conservation efforts, DNS not only reduces the financial burden on these countries, but also empowers them to protect their ecosystems and enhance climate resilience. This approach aligns with the global imperative of addressing climate change and fostering sustainable development, benefiting both the countries involved and the wider world. It also contrasts traditional approaches to debt restructuring, which promote austerity measures that take money out of local economies and undermine, rather than further, domestic development.

APPLYING THE DNS MECHANISM

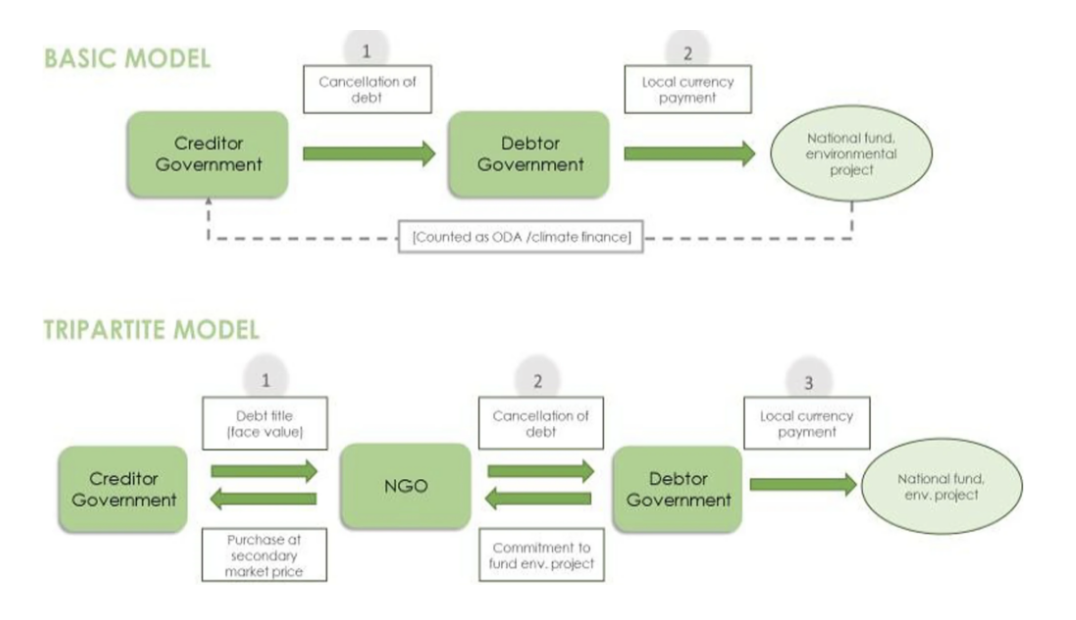

The practical application of the DNS mechanism operates primarily through two distinct modes. The first mode is the fundamental bilateral approach, where debt relief transpires directly between one or more creditor governments and the debtor nation's government. In essence, this mode equates to the former providing the latter with specialized assistance funding earmarked for environmental preservation. Conversely, the second mode is orchestrated by third-party international non-governmental organizations (NGOs). In this arrangement, these entities acquire debt securities from secondary markets, subsequently affecting debt reductions on behalf of the debtor country in exchange for concrete environmental commitments. Importantly, the pricing dynamics in secondary markets predominantly hinge on the probability of the debtor nation's full debt repayment [7].

Source: Lukšić, Igor, Bošković, Biljana, Novikova, Anna, et al. (2022) [8]

Case introduction of basic model:

In 1992, Poland and the Paris Club reached a significant bilateral debt conversion agreement, which led to one of the largest debt-for-nature swaps of the 20th century. During the 1980s, the Paris Club evolved from an informal creditors group to an international debt restructuring mechanism, and in the early 1990s introduced provisions to allow debtor nations to conduct debt-for-nature swaps using their own domestic currency. Poland, an early participant, owed the Paris Club about $3 billion. The Paris Club granted Poland a 50% debt reduction and an additional bilateral debt exchange of up to 10% after the reduction. The surplus reduction was distributed to the newly established EcoFund, which aims to address critical environmental issues in Poland [9].

Case introduction of tripartite model:

In a recent and significant example of the tripartite model, the United States International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) and the Ecuadorian government collaborated on a commercial debt-for-nature swap in May 2023. This marked the largest global debt-for-nature transaction to date. Ecuador converted $1.628 billion in sovereign bonds into a $656 million loan. The DFC provided $656 million in political risk insurance, supported by a $85 million guarantee from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), and over 50% reinsurance from a consortium of 11 private insurers. The loan funds came from the Galápagos Marine Bond, issued by Credit Suisse, maturing in 2041 and rated as investment-grade by Moody's. In return, Ecuador committed to invest approximately $323 million in Galápagos Islands marine conservation over the next 18 years [10].

IMPLEMENTATION SUGGESTIONS FOR THE DNS MECHANISM

Despite its success in some cases, the debt-for-nature swap mechanism's implementation involves complexities and challenges. One primary challenge is high transaction costs due to the involvement of multiple stakeholders like debtors, creditors, donors, and NGOs. Another is long preparation and negotiation processes, which, coupled with differences in opinion, can reduce efficiency. Additionally, potential fiscal crises as well as conflicts caused by environmental protection measures that infringe on the interests of local or Indigenous communities may also negatively affect the ability of DNS mechanisms to promote national and local well-being. Given these issues, this article proposes improved implementation management measures.

Firstly, establishing a strong policy framework for debt-for-nature swaps is crucial. In this regard, explicitly defining key elements, such as debt types, eligibility criteria for debtor countries, fund management and supervision, and utilization scope is advisable. Moreover, ensuring that the agreements align with the environmental goals of debtor countries is of utmost importance.

Secondly, it is crucial to create a multilateral cooperation platform that enables joint financing. The governing bodies of debt-for-nature swap mechanisms should team up with Paris Club members, domestic and international financial institutions, foundations, and non-governmental organizations to establish such a platform. This would not only enhance internal capacity but also draw investment from both domestic and international public and private sectors. For example, market incentives such as carbon emission trading credits may be extended to encourage social capital involvement.

Thirdly, while addressing existing debt issues, it is imperative to establish more rigorous project assessment requirements to prevent the emergence of new debt problems. It is recommended that creditor country financial institutions and enterprises employ methods such as Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) and Environmental and Social Management Systems (ESMS) to evaluate investment projects. Additionally, advocating for stringent environmental and biodiversity risk assessments can help avert fresh debt challenges.

Finally, a very crucial point is to ensure that these initiatives not only meet the needs of debtor governments but also take into account the welfare of local populations in debtor countries. Environmental protection organizations have been criticized regarding the negative impacts that Western conservation models have had on Indigenous and local communities, often referred to as 'fortress conservation' [11]. One possible method to mitigate similar risks while promoting the sustainable transition is to incorporate safeguards and community engagement mechanisms into the implementation process. Local and Indigenous communities often have valuable traditional knowledge about their ecosystems, and their involvement can lead to more effective and equitable conservation efforts [12]. Furthermore, revenue-sharing mechanisms can be established to ensure that local populations benefit directly from the conservation initiatives, providing economic incentives for their support and cooperation.

CONCLUSION

Unlike the current mainstream debt restructuring methods, such as interest rate cuts and maturity extensions that are plagued by limited impact and uncertainty risks, DNS mechanisms promise more effective debt relief with guarantee mechanisms and environmental and developmental benefits. They help debtor countries cope with climate risks while restructuring their debt, reducing the burden on countries bearing the brunt of both the debt and climate crises. However, the implementation of this approach is fraught with challenges such as high transaction costs, complexities in the execution of environmental projects, and the possibility of injustices arising at the local-level. Addressing these issues calls for closer collaboration among creditor countries, debtor countries, and international organizations. This entails establishing a clear policy framework, creating a wide-reaching platform for multilateral cooperation, and ensuring agreements align with the needs of debtor nations and their local populations, thereby promoting environmental justice and reducing inequality.

With the simultaneous intensification of debt-burdens, climate change, and environmental concerns, debt-for-nature swaps are poised to become a crucial tool in addressing these challenges. In the future, further research and refinement of the mechanism's operational modalities can promote greater participation by nations. Such progress would greatly contribute to the global goals of environmental conservation and sustainable development, while reducing the global inequalities perpetuated by rising debt service pressures.

References:

[1] IMF. World Economic Outlook and Fiscal Monitor. 2023. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/April/select-countries?grp=2200&sg=All-countries/Emerging-market-and-developing-economies

[2] World Bank. World Development Indicators. 2023. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

[3] Fitch Ratings. 2023. "Sovereign Defaults Are at Record High." https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/sovereign-defaults-at-record-high-29-03-2023

[4] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). "Debt-for-Environment Swaps." OECD official website. Accessed: September 2023. https://www.oecd.org/env/outreach/debt-for-environmentswaps.htm

[5] Visser, Dana R., and Guillermo A. Mendoza. "Debt-for-Nature Swaps in Latin America." Journal of Forestry 92, no. 6, 1994: 13-16. https://academic.oup.com/jof/article-abstract/92/6/13/4635995

[6] Hebbale, Chetan. "Debt-for-Climate Swaps: Analyzing Climate Vulnerability and Debt Sustainability." RPubs, Accessed: September 2023. https://rpubs.com/chebbale/973245

[7] Sheikh, Pervaze A. "Debt-for-Nature Initiatives and the Tropical Forest Conservation Act (TFCA): Status and Implementation."2016. Congressional Research Service, 2. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/RL31286.pdf

[8] Lukšić, Igor, Biljana Bošković, Anna Novikova, et al. "Innovative Financing of the Sustainable Development Goals in the Countries of the Western Balkans." 2022. Energ Sustain Soc 12, no. 15. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13705-022-00340-w

[9] OECD. "Lessons Learnt from Experience with Debt-for-Environment Swaps in Economies in Transition." OECD Papers 7, no. 5 (2007). https://www.oecd.org/env/outreach/39352290.pdf

[10] U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC). "Financial Close Reached in Largest Debt Conversion for Marine Conservation to Protect the Galápagos." DFC official website. May 2023. Accessed: September 2023. https://www.dfc.gov/media/press-releases/financial-close-reached-largest-debt-conversion-marine-conservation-protect

[11] Kabra, A. “Ecological Critiques of Exclusionary Conservation.” Ecology, Economy and Society-The INSEE Journal. 2019. 2(2354-2020-1298). https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/304020/files/EES%201-2%20009-026.pdf

[12] Alexander, Zaitchik. “How conservation became colonialism.”Foreign Policy. July 16, 2018.Accessed: September 2023. https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/07/16/how-conservation-became-colonialism-environment-indigenous-people-ecuador-mining/

Photo Credit: Filipe Frazao, Getty Images, Licensed with Canva Pro