BY EMMA SLATER

Emma Slater is a first-year M.A. student at the SAIS Europe campus.

Introduction:

Despite thousands of Chinese workers and tourists flying in and out of Cambodia every month, the country has recorded only 124 cases of coronavirus (as of May 28, 2020) out of 12,378 tests (between January and the start of May).[1] The cases have predominantly been based in the capital of Phnom Penh and cities of Sihanoukville and Kampong Cham, but 13 of Cambodia’s 25 provinces have had recorded cases.[2] With 0.8 hospital beds per 1,000 people Cambodia’s hospital system does not have a high capacity for COVID-19 cases.[3] However, by March they had prepared all national hospitals for COVID-19, suspended travel via waterways and a restriction on visitors from coronavirus hotspots (excluding China).[4] From April 10, the government prohibited travel across provinces and between districts for one week and has advised social distancing, but with only 2 new cases since April 12, priority has been given to allowing economic activities to re-start. Due to the economy’s susceptibility to supply and demand shocks from the global economy, the government has predominantly focused on economic measures. However, the long-standing president Hun Sen has also used the crisis to push wide-reaching controls over media outlets through parliament.[5]

1. Economic Growth Impacts

Cambodia is an export driven economy, heavily impacted by declining demand for exports (exports accounted for 61.6 percent of GDP in 2018).[6] Close linkages with both the Chinese and US economies mean the economic impact of the coronavirus has already decelerated a number of Cambodia’s key industries including tourism, garment manufacturing, and construction.

1.1 Estimated GDP Growth Impact

It is expected that the economic impacts of coronavirus will reduce GDP growth in 2020 to between -1.0 to 2.5 percent, down from 7.1 percent in 2019 (Table 1). During the 2008 financial crisis, GDP growth dropped from 6.7 percent in 2008 to 0.9 percent in 2009. Cambodia has become more resilient since then, diversifying slightly in exports and export partners;[7] however, their increased reliance on Chinese tourism, imports and capital has resulted in an increased sensitivity to China’s slowdown.

All estimations show recovery of growth by the end of 2021 (similar to the 2010 rally to 6.0 percent) based on the projected recovery of the global economy and the related demand and supply.

1.2 Export Demand Shock

1.2.1 Tourism Industry

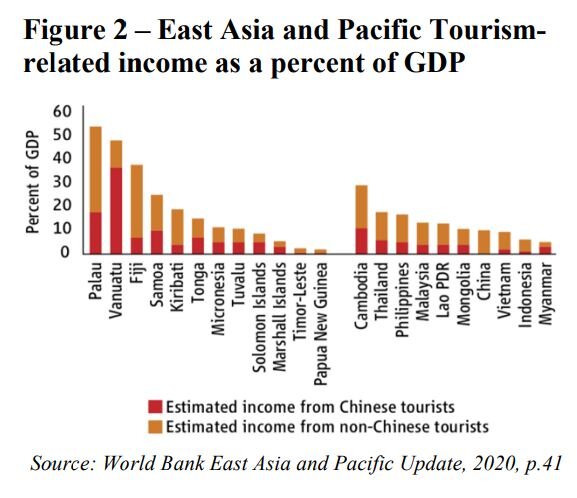

Tourism revenues contributed to between 13.5- 15% of GDP since 2011,[8] and China has become an increasingly important part of tourism growth in Cambodia (Figure 1). Compared to most peers, Cambodia is more vulnerable to a loss of tourism from China, based on the latest data available in April 2020 (Figure 2).

As a result of the coronavirus outbreak in China, tourism has already dropped substantially. There was a 37.2 percent drop in foreign visits to the Angkor Wat complex during the first two months of 2020.[9]Since March, an estimated 20 percent of the world’s population’s movement has been restricted, putting continued strain on the tourism sector.[10] However, the expected return of tourists in 2021 will facilitate a rebound.

1.2.2 Garment Industry

Garments account for 80 percent of export earnings in Cambodia, and the industry represents about 16 percent of GDP.[11] The US and the EU are the largest garment export partners (Figures 3 and 4), and the economic impact of lock-down restrictions in both regions is already impacting the industry. Cambodia’s Garment Manufacturers Association has reported order cancellations and reductions and expects factory closures throughout 2020 as a result.[12] In addition to reductions in the quantity of garments demanded, price drops in the end market for garments are likely to further impact the industry.[13]

The 2008 financial crisis created a similar negative demand shock to the garment industry, particularly from the US (Figure 3), resulting in negative growth in the industry in 2009, and pushing national GDP growth down to 0.9 percent.

The IMF estimates a 5.9 percent contraction in US GDP implying a similar drop in demand will occur in 2020.[14] This will be compounded with the EU’s partial withdrawal of the Everything But Arms (EBA) agreement in August 2020.[15] However, expected US recovery in 2021 should drive a rebound in Cambodia by 2021, as it did in 2010.[16]

1.3 Import Supply Shock

1.3.1 Garment Industry

The garment industry is also highly reliant on imports of raw materials from China (Figure 5). Cambodia’s garment factories began closing in March as a result of decreased imports from Chinese factories.[17] By April 91 percent of factories were shut down.[18] However, China’s gradual reopening of factories beginning in April 2020 will reduce the supply pressure on factories. As of mid-April, limited to no restrictions have been put on the supply of workers in Cambodia, to the contrary, Hun Sen has advised workers to continue at work.[19]

1.3.2 Construction Industry

The construction industry has become an instrumental part of the economy, contributing to over a third of Cambodia’s GDP growth in 2019.[20] However, it too relies on Chinese imports of raw materials. Imports of steel dropped by 41.3 percent in January 2020 compared to January 2019 and as a result, construction activity weakened.[21] Decreasing investment will also lead to decreased performance in the construction industry.

1.4 Current Account Deficit Surge

Cambodia’s current account deficit increased from around 8 percent of GDP in 2017 to around 12.5 percent in 2019,[22] driven by significant increases in the imports of construction materials, fuels and vehicles. The IMF expects this to rise further to 22 percent in 2020 before reducing in 2021,[23] driven by the appreciation of the USD, which Cambodia’s currency is pegged to, and the expected drop in export demand.

High previous FDI inflows have accumulated approximately 8 months of reserves, higher than many peers,[24] which will help fill the initial shortfall and Cambodia is in a strong position to find additional funding from the capital markets. The country has not yet requested funding from the IMF, however financing the growing current account deficit will dampen GDP growth in 2020 and 2021.

1.5 Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Drop Risk

Cambodia is highly reliant on FDI inflows from China (Table 2), particularly in the construction, real estate and garment industries.[25] FDI funded construction contracts dropped by 9.7 percent in 2019 throwing the industry’s immediate growth into question.[26] Further drops in FDI will slow GDP growth.

2. Distributional Impacts

The largest impacts will be felt by those working in the garment, construction and tourism industries and those in the informal sector with little access to state support. The contraction of the garment sector in particularly is likely to increase poverty rates of those working in the sector, by over 20 percentage.[27]

The informal sector in Cambodia is estimated to employ a significant proportion of the working population.[28] Many will lose work, particularly those working supporting tourism or household consumption. Those working in the informal sector are more vulnerable to negative economic shocks with little formal access to state help.

80 percent of the population are rural and are reliant on agriculture and local self-employment, which will be impacted less directly. A ban on rice exports, a growing drought, and a decrease in industrial remittances[29] are expected to slow down rural poverty reduction.

Cambodia is a key rice exporter and rice prices have remained stable through 2020.[30] However, to ensure local food supplies, Cambodia has announced a ban on some rice exports.[31] There is likely to be a slight negative impact on the agricultural sector. Additionally, increasing drought conditions recorded in the lower Mekong delta in early 2020 will further strain the rural communities.[32]

Furthermore, the loss of domestic remittances from industrial workers in the garment and construction industries abroad is likely to affect both urban and rural communities significantly.

Approximately two thirds of the population above the national poverty line remain below the higher international poverty line (USD 5.50 a day PPP)[33] and are highly susceptible to healthcare costs and loss of employment.

The closure of schools from mid-March is expected to affect the approximately one third of children who rely on school feeding programs.[34] This will put greater pressure on households near the poverty line and have longer term implications along with the educational impacts. Approximately 34% of Cambodians have access to the internet and the online learning and working opportunities it brings, predominantly the wealthier households. This could exacerbate inequality in the country.

3. Possibilities for Expansionary Fiscal Policies

Cambodia’s recent strong fiscal revenue collection has strengthened its position and its ability to implement countercyclical fiscal policies. [35] However, as with many states, tax revenue is expected to drop as business revenue declines and a series of tax cuts are implemented.[36] The fiscal surplus of 0.5 percent of GDP is expected to become a deficit of 3 percent of GDP in 2020 before reducing to a deficit of 0.4 in 2021.[37]

Public government gross debt was at a low 30 percent of GDP (Table 3), and debt carrying capacity is considered strong by the IMF with debt-service-to-exports at around 1.6 percent of GDP.[38]

From this strong position, the USD 800m to USD 2bn[39] (0.3 to 0.8 percent of 2018 GDP[40]) fiscal package announced seems reasonable. However, the government does not have the infrastructure to reach many of those most in need and support the scale of unemployment benefit needed. Many of Cambodia’s population are unbanked and unregistered, which makes dispersion of social welfare support challenging.

Government spending has thus far focused on the immediate impact, supporting the worst hit tourism, garment and footwear sectors through tax concessions and relief,[41] special interest loans,[42] and support for wage payments for staff otherwise laid-off[43] (estimated up to USD 42m at $70 per up to 600,000 workers in the garment sector). However, increased social protection programs aimed at the poor and unemployed have been announced, as well as retraining, upskilling programs and job search services.[44]

4. Possibilities for Expansionary Monetary Policies

Inflation has remained stable just above 2 percent for the past few years,[45] giving the central bank space for expansionary monetary measures, including easing restrictions on borrowing to support liquidity in the economy. By cutting the interest rate on their Liquidity Providing Collateralized Operations (and their collateral), they decreased banks’ funding costs (in Riel). Similarly, lowering national reserve requirements has also freed up money to be lent out.[46]

However, easing access to private credit needs to be monitored closely to avoid financial instability and excessive risk. The Bank updated loan guidelines to financial institutions for borrowers experiencing financial difficulties in priority sectors (tourism, garments, construction, transportation and logistics)[47] to provide support, but should regularly update risk evaluations.

Monetary stimulus through asset purchases has not yet been considered or announced, but Cambodia’s money supply is highly dependent on foreign currency deposits, about 83 percent of liquidity, increasing its vulnerability if those deposits dry up.[48]

However, the widening current account deficit will put significant downward pressure on the Cambodian Riel’s real effective exchange rate to depreciate against the appreciating US dollar. If the Cambodian authorities want to maintain the Riel peg to the US dollar, they will need to intervene significantly in the currency market to maintain it.

Conclusion:

Cambodia’s reliance on exports to the US and Europe and imports and FDI from China have made it uniquely sensitive to the economic consequences of the global coronavirus crisis. Its large informal sector, particularly in the tourism industry, will pose challenges for welfare responses. However, despite the challenges of a significant drop in export demand and the growing current account deficit, the country is in a strong fiscal position to manage the crisis. Swift and targeted monetary and fiscal responses will assist in Cambodia’s recovery. Nevertheless, this recovery will be largely dependent on whether tourism and demand for garment exports will rebound as expected in 2021.

[1] https://english.cambodiadaily.com/health/covid-19-testing-drops-by-half-as-no-new-cases-reported-for-22-days-163671/

[2] https://www.khmertimeskh.com/715807/cambodias-covid-19-pandemic-still-in-first-stage-with-entry-lockdown-playing-a-part-in-containment/

[3] World Bank database - https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.BEDS.ZS

[4] Note the restrictions on entry were relaxed on May 20, 2020

[5] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-cambodia/cambodia-adopts-law-to-allow-for-emergency-powers-to-tackle-coronavirus-idUSKCN21S0IW

[6] World Bank, Database, accessed April 26, 2020

[7] World Bank, Systematic Country Diagnostic Cambodia, 2017, p.22.

[8] World Bank, TCData360 database, accessed April 19, 2020

[9] World Bank, East Asia and Pacific Economic Update, April 2020, p.160

[10] Dominic Gilbert, “Which countries are under lockdown and is it working?”, The Telegraph, 19 April 2020

[11] Vasundhara Rastogi, “Cambodia’s Garment Manufacturing Industry”, ASEAN Briefing, 2018

[12] David Pierson, “New clothes pile up at Cambodian factories”, LA Times, 15 April 2020

[13] James Sillars, “Coronavirus: Plunge in clothing and fuel costs help inflation 1.5%”, Sky News, 22 April 2020

[14] IMF, World Economic Outlook, April 2020, p.ix

[15] Asian Development Bank, Asian Development Outlook 2020, April 2020, p.267

[16] World Bank, World Bank database, accessed 19 April 2020

[17] Tomoya Onishi, “Cambodia’s garment industry hangs by a thread”, Nikkei Asian Review, 6 March 2020

[18] Reuters, “Cambodia says 91 garment factories suspend work due to coronavirus”, Reuters, 1 April 2020

[19] Pearson, LA Times, 2020.

[20] World Bank, 2020, p.161

[21] World Bank, 2020, p.160

[22] IMF, 2019, p.28, 35

[23] IMF, World Economic Outlook Database, accessed 19 April 2020

[24] World Bank, 2020, p.15

[25] World Bank, 2020, p.73

[26] World Bank, 2020, p.160

[27] World Bank, 2020, p.63

[28] World Bank, Cambodia Investment Climate Assessment 2014, 2015, p.76

[29] World Bank Systemic Diagnostic Report, 2017, p.40

[30] Business Insider, Commodities Prices – Rice Price, accessed April 19, 2020

[31] Manisha Vepa. “Cambodia to ban some rice exports starting today,” Foreign Brief, 5 April 2020

[32] Hannah Beech. “China Limited the Mekong’s Flow”, The New York Times, 13 April 2020; UNITAR, Preliminary Drought Assessment in the Lower Mekong Basin, 13 February 2020

[33] World Bank, 2017, p.41

[34] IMF, Policy responses to COVID-19, website, accessed 19 April 2020; World Bank, 2020, p.68

[35] IMF, 2019, p.7

[36] World Bank, 2020, p.161

[37] World Bank, 2020, p.162

[38] IMF, 2019, p.28

[39] Kann Vicheika, “Cambodian Government Allocates Up to $2 Billion for Economic Fallout from Coronavirus”, VOA Cambodia, 10 March 2020

[40] World Bank, World Bank database, accessed 19 April 2020

[41] World Bank, 2020, p.31

[42] IMF, Policy responses to COVID-19, website, accessed 19 April 2020

[43] David Sen, “Each laid-off worker to get $70 a month”, Khmer Times, 8 April 2020.

[44] IMF, Policy responses to COVID-19, website, accessed 19 April 2020; World Bank, 2020, p.32

[45] IMF, World Economic Outlook Database, accessed 19 April 2020

[46] IMF, Policy responses to COVID-19, website, accessed 19 April 2020

[47] Ibid.

[48] Asian Development Bank, 2020, p.267

Complete References

Databases

World Bank - https://data.worldbank.org/ & https://data.worldbank.org/country/cambodia

World Bank TC Data - https://tcdata360.worldbank.org/indicators/tot.direct.gdp?country=KHM&indicator=24648&countries=BRA&viz=line_chart&years=1995,2028

Business Insider, Commodity Prices - https://markets.businessinsider.com/commodities/riceprice

IMF World Economic Outlook Database - https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2020/01/weodata/weoselgr.aspx

Asian Development Bank, Asian Development Outlook 2020, April 2020 https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/575626/ado2020.pdf

Beech, Hannah. “China Limited the Mekong’s Flow. Other Countries Suffered a Drought”, The New York Times, 13 April 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/13/world/asia/china-mekongdrought.html

Gilbert, Dominic. “Which countries are under lockdown and is it working?”, The Telegraph, 19 April 2020. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/04/16/countries-in-lockdown-denmark-germany/

International Monetary Fund, 2019 Article 19 Consultation, Washington DC, December 2019.

International Monetary Fund, Policy responses to COVID-19, website, accessed 19 April 2020. https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19#C

International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, Washington DC, April 2020 Onishi, Tomoya. “Cambodia’s garment industry hangs by a thread”, Nikkei Asian Review, 6 March 2020 https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Coronavirus/Cambodia-s-garment-industry-hangs-by-athread

Pierson, David. “New clothes pile up at Cambodian factories. Coronavirus forces U.S. brands to cancel orders”, LA Times, 15 April 2020. https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-04-15/coronavirus-cambodia-garment-industry

Rastogi, Vasundhara. “Cambodia’s Garment Manufacturing Industry”, ASEAN Briefing, 1 November 2018. https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/cambodias-garment-manufacturing-industry/

Reuters, “Cambodia says 91 garment factories suspend work due to coronavirus”, Reuters, 1 April 2020 https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-cambodia-garments/cambodia-says91-garment-factories-suspend-work-due-to-coronavirus-61500-workers-affectedidUSL4N2BP3KY

Sen, David. “Each laid-off worker to get $70 a month”, Khmer Times, 8 April 2020. https://www.khmertimeskh.com/710752/each-laid-off-worker-to-get-70-a-month/

Sillars, James. “Coronavirus: Plunge in clothing and fuel costs help inflation 1.5%”, Sky News, 22 April 2020 https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-plunge-in-clothing-and-fuel-costs-helpinflation-ease-to-1-5-11976847

UNITAR, Preliminary Drought Assessment in the Lower Mekong Basin, 13 February 2020. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/UNOSAT_Preliminary_Assessment_Rep ort_MK_Basin_Drought_V04.pdf

Vepa, Manisha. “Cambodia to ban some rice exports starting today to ensure local food security”, Foreign Brief, 5 April 2020. https://foreignbrief.com/daily-news/cambodia-to-ban-some-riceexports-starting-today-to-ensure-local-food-security/

Vicheika, Kann. “Cambodian Government Allocates Up to $2 Billion for Economic Fallout from Coronavirus”, VOA Cambodia, 10 March 2020 https://www.voacambodia.com/a/cambodiangovernment-allocates-up-to-2-billion-dollars-for-economic-fallout-fromcoronavirus/5322557.html

World Bank, “Approves $20 Million for Cambodia’s COVID-19 Response”, World Bank Press Release, 2 April 2020 https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/04/02/worldbank-approves-20-million-for-cambodias-covid-19-coronavirus-response

World Bank, Cambodia Investment Climate Assessment 2014 – Creating opportunities for firms in Cambodia, Phnom Penh, 2015 http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/251591468236679212/pdf/940060WP0Box380sses sment020140FINAL.pdf

World Bank, East Asia and Pacific Economic Update April 2020, Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, 2020. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33477

World Bank, Systematic Country Diagnostic 2017: Cambodia - Sustaining strong growth for the benefit of all, Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, 2017 https://hubs.worldbank.org/docs/imagebank/pages/docprofile.aspx?nodeid=27520556

PHOTO CREDIT: Free use image from Canva Pro.