BY MORITZ OSTERHUBER

Moritz Osterhuber is a second-year SAIS student from Germany concentrating in Latin American studies who spent the first year of the MA program at SAIS Europe in Bologna.

Chile is a commercial success story in Latin America, but deep structural issues hinder the country’s development. In the 1980s, Chile shook off a scarring economic crisis through productivity growth and succeeded in democratizing key governance structures. Rising commodity prices in the early 2000s facilitated far-reaching economic modernization that propelled Chile to become the first OECD member in Latin America.

High economic growth since the 1980s turned the country into an economic powerhouse and heralded a future of prosperity for its citizens. Today, however, that future remains unattainable for many Chileans as benefits from growth gravitate toward the privileged in a system in which socioeconomic inequality is endemic. Wide segments of society continue to be excluded from high-quality education and health care, whilst widespread inequality of opportunity clogs channels of social mobility. The Indigenous, female, and rural biases in poverty add to the internal divide of the country. Previously dormant grievances found a powerful outlet in October 2019, when a hike of subway fares in Santiago turned into a larger indictment of exclusion and inequity in the country. The ensuing protests prompted clashes with the military and elicited a reform pledge from President Sebastián Piñera.

The COVID-19 pandemic gripped Chile in the midst of its reflection on an uneasy reality of socioeconomic inequality. The first local outbreaks developed by mid-March after cases were imported from Europe. On March 16th, the government announced a state of catastrophe, shut Chile’s borders, restricted the movement of its citizens, and implemented a night-time curfew. It pursued a flexible containment approach that would see harsher local lockdowns in areas with concentrated COVID-19 flare-ups (Castiglioni, 2020). While Chile was able to hold infection and death rates stable at low levels through April 2020, daily infection rates began to grow exponentially in May. Warned by the excruciating experiences of other countries, the government imposed one of the strictest lockdowns worldwide on the greater Santiago area on May 14th. Commuting domestic workers had previously transmitted the virus to lower-income areas where living arrangements complicated social distancing and where mobility remained comparatively high (Vergara Perucich et al., 2020; Vallejos, 2020). In May, a correlation emerged whereby contagion propensity was linked to income, shedding light on the appalling socioeconomic dimension of the pandemic in Chile (Jiménez Molina et al., 2020).

As infection rates stayed stubbornly high during the Chilean winter, the pandemic’s enormous economic cost was increasingly laid bare. President Sebastián Piñera announced a careful and phased resumption of public life on July 19th, placing the Chilean containment measures among the longest and most-severe on the planet. The economic toll of the pandemic came in the form of a dual shock for Chile: While the comparatively long period of paralysis stifled consumption and investment activity at home, turmoil on international commodity markets imported distress and amplified the strain on the economy. Despite recent efforts to diversify its economy, Chile remains dependent on exports from the copper industry, which nurtures a large ancillary network of suppliers. The depressed long-term outlook for copper prices therefore has far-reaching ripple effects for employment, wages, government revenue, and national income. Foreign markets will also partly dictate the pace of recovery as macroeconomic stabilization fell short of sterilizing GDP growth from volatility on commodity markets (De Gregorio & Labbé, 2011). Similarly to the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008, government revenues are set to plunge in 2020, while Chile will need unprecedented fiscal spending to satisfy potentially large balance of payments needs, support economic activity, and reduce the economic distress of vulnerable groups. The economic reverberations of the 2019 protests add to a primary deficit that is quickly growing in 2020. However, Chile’s sovereign wealth fund, its track record of fiscal discipline, and the sustained market access mean that the country is well-positioned to face these extraordinary funding needs.

Since March 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic has profoundly affected finance, trade, and economic activity in Chile (WB, 2020). Fueled by the world’s largest known copper reserves, Chile is a commodity-based, export-driven economy. Its export value measured as a share of GDP (28.8 percent) trails Germany but far exceeds those of the United States (12.2 percent) and regional peers, such as Peru (25.4 percent) and Argentina (14.3 percent). Chile’s export dependence heightens the country’s exposure to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic because its economic performance is interlaced with patterns of global demand. Among the most important markets for Chile are the large Asian economies of China, Japan, and South Korea, accounting for 41.9 percent of total exports. The United States (15.0 percent) and regional Latin American peers (12.3 percent) follow Asia as Chile’s prime commercial partners, whilst European countries assume a subordinate, yet not insignificant, role. Commerce with these markets is dominated by copper and other minerals, which underlines the importance of copper prices for proceeds, employment, and investment in Chile’s export industries (Figure 1). Chile’s terms of trade, a measure of relative export prices, depend to a large extent on copper prices and influence the country’s growth potential.

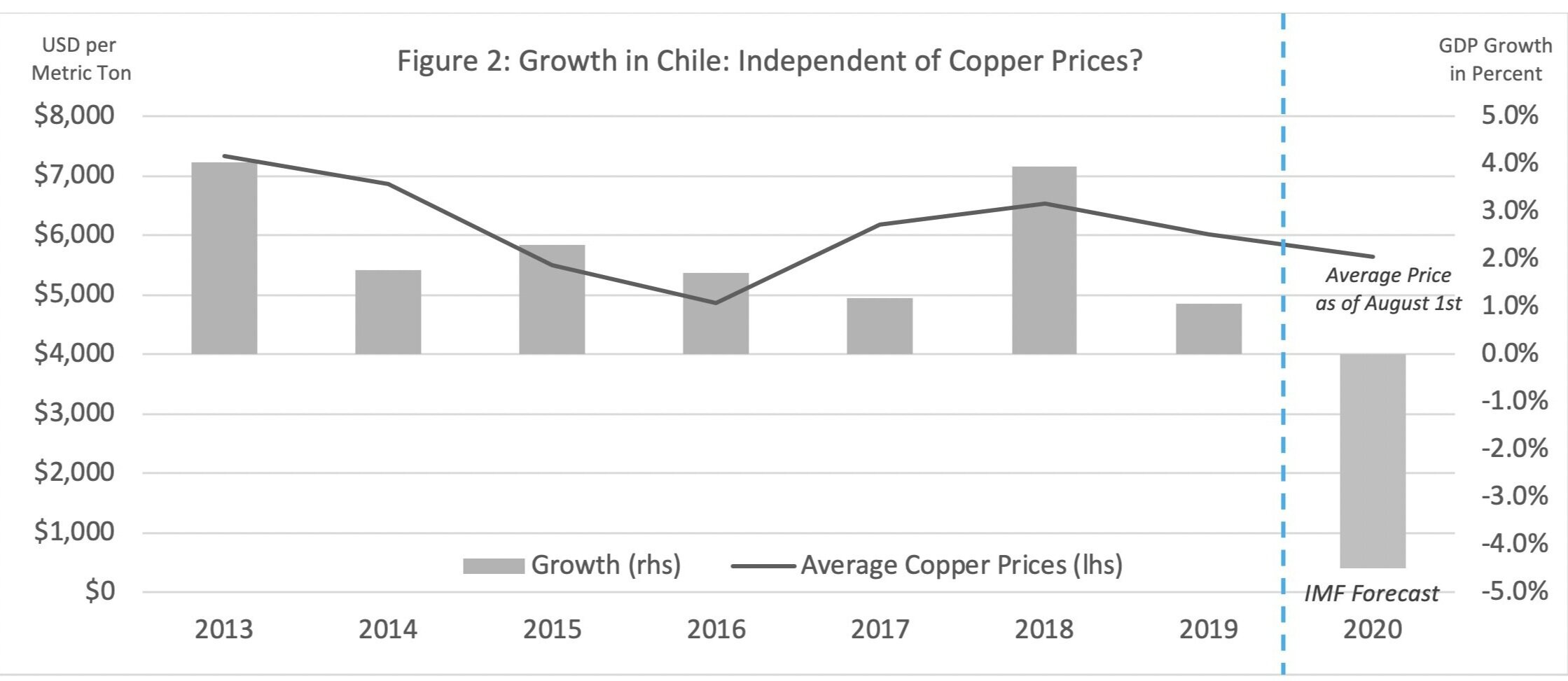

Source: Author’s elaboration of ITC Trade Map data

Chile will undergo a deep recession and will likely see its national income decrease by 4.5 percent in 2020 (Figure 2), after which the economy is projected to return to a positive growth rate of 5.3 percent in 2021 (IMF, 2020c, p.22). Late last year, growth forecasts for 2020 had already been scaled down to between 1 and 1.5 percent due to the reverberations of the October protests (Gomez, 2019). Similar to other countries, the forfeited domestic consumption and investment during lockdown are the primary reasons for negative GDP growth in 2020. Limited capacity for remote work will further entrench ruptures of employer-employee relations in the labor market and protract the recovery particularly in lesser developed regions and sectors relying on in-person interaction. Moreover, depressed outlooks for commodity prices compound the recession in Chile since they have an asymmetric impact on the country’s current account: While commodities account for 55 percent of exports, they make up only 20 percent of imports. This divergence caused Chile’s terms of trade to fall particularly in March and April 2020. Although the flexible exchange rate partially absorbed volatility on foreign markets, GDP growth and the fiscal balance in particular remain sensitive to price swings on copper markets (De Gregorio & Labbé, 2011).

Source: Chisari et al. (2019), page 17.

Chile’s dependence on copper exports will amplify the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. Chisari et al. (2019) use a computable general equilibrium model (CGE) to estimate the impact of commodity price fluctuations on macroeconomic indicators (Table 1). They show that Chile’s economy (GDP) and overall welfare (H1&H2) contract significantly when copper prices fall (and more so than in Argentina and Brazil). This is because declining terms of trade curtail Chileans’ purchasing power in international markets and make a substantial dent into revenues of the export sector. In the case of the recent drop in copper prices, this will lead to a sizeable downward adjustment of wages and will precipitate lay-offs specifically in the mining sector, reversing a trend toward more labor-intensive mining operations. In fact, mines already operate with 30-60 percent fewer personnel (Trejo, 2020) and overall unemployment is projected to increase by more than 30 percent in 2020, to 9.7 percent, before recovering slightly in 2021 to 8.9 percent (IMF, 2020c). As Chileans have less disposable income, domestic consumption will decrease and transmit the external shock to the domestic economy. Moreover, as less profitable mines become unviable as a result of global supply overhang, large industrial clusters around mining operations and refineries will also face reduced demand throughout 2020 and 2021. Yet, the CGE model (Chisari et al., 2020) also shows that a downward adjustment of wages (equal in effect to a currency devaluation), despite hurting domestic consumption, reduces the depth of the recession. This underscores that currency depreciation, similar to the terms of trade shock in 2011, may be a key buffer protecting the Chilean economy.

Source: Author’s elaboration of data from the World Bank and Market Insider

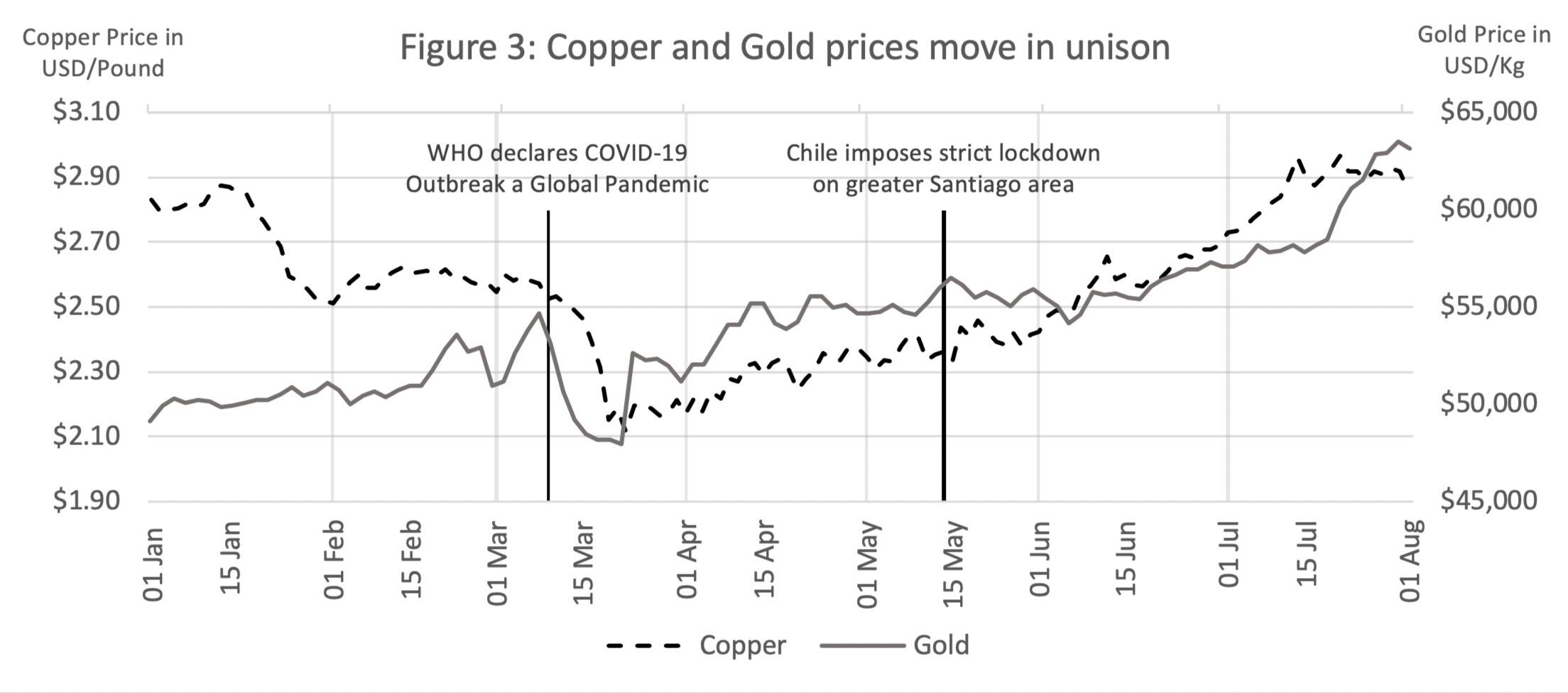

Copper prices plunged in March 2020 as the staggering scope of the COVID-19 pandemic became clear (Figure 3). As an essential material in construction, electronics, and engine manufacturing, demand for copper was particularly susceptible to closures in manufacturing plants and construction moratoria announced across the Middle East, Europe, and the United States in early 2020 (Pollock, 2020). China, consumer of roughly 50 percent of global extraction and single most important buyer of Chilean copper, had been slow to ramp up manufacturing output even as it moved to reopen its economy in March and April 2020. Moreover, the Chinese fiscal stimulus and public infrastructure programs trailed expectations and failed to bolster global copper prices in March (The Economist, 2020a). Prices were also pushed down by exceptionally elevated uncertainty about the future trajectory of the crisis as the pandemic had yet to peak in many developing and emerging economies. As a result, international copper prices fell by more than 25 percent between January and March 2020. For Chile, 55 percent of whose exports depend on copper and minerals, this resulted in a stark decline of the country’s terms of trade and a thus deteriorating external condition.

Since April 2020 copper prices have staged an unexpected, remarkable comeback. Prices rose gradually since April to make good the pandemic-inflicted losses by early June and supersede their previous year-high in mid-July. The ascent was propelled by a surprisingly dynamic construction sector in China that reached pre-crisis levels in April and a partial return of European and American manufacturing in June and July (Eurostat, 2020; International Construction, 2020). The price boom was also driven by speculation and a return of funds to the copper market. Investors limited their short positions over April and May and considerably expanded their long positions in the summer as Chinese demand solidified alongside fears of future supply disruptions and bottlenecks (Home, 2020). While ‘skeleton crews’ in Chilean mines have been able to keep the pace of extraction roughly stable, some mines in neighboring Peru had to close during the pandemic, adding to a bullish price outlook (Harris, 2020). Operating Chilean mines with staff at the lower bound, however, likely promoted negligence of crucial tasks such as maintenance, suggesting that current supply levels cannot be maintained in the longer-run (Sherwood & Ramos Miranda, 2020). Moreover, health concerns additionally stoke fears that the pandemic may still take a toll on Chilean mining as infections among the workforce of Chile’s largest copper producer Codelco topped 3,200 cases in July (Reuters, 2020).

The unusual trajectories of gold and copper prices suggest that copper markets have lost their role as pulse monitor of the global economy. Copper prices are traditionally interpreted as a metric for the health of the global economy since robust prices suggest confidence in the global manufacturing and construction sectors. Rising prices are also associated with increasing global risk appetite as investors move into corporate bonds and stocks, including in emerging markets. Rising gold prices, on the other hand, are typically associated with the opposite sentiment: As a measure of market fear and the depth of a crisis, they indicate the propensity for investors to abandon risk and take refuge in ‘safe-haven’ assets such as metals, reserve currencies, and government debt. Copper and gold prices therefore traditionally diverge amid the uncertainty and volatility on the heels of disruptive events. Over recent months, however, copper and gold prices moved almost in unison, suggesting that the signaling character of copper markets for global distress is momentarily impaired. Despite recovering capital flows into emerging economies and a phased reopening of economies worldwide, copper prices likely overestimate the health and recovery path of the global economy. Moreover, current prices seem to be at odds with the downside risks of a second wave, a combination of debt and financial crisis, and depressed income and output levels in the longer-term.

Source: Author’s elaboration of data from Market Insider and Bullion Vault

Copper prices are unlikely to sustain their currently elevated levels through 2020 and 2021 even if the global economic recovery picks up momentum. Looking back at earlier forecasts from April and May 2020 of a swift recovery after COVID-19 lockdowns, one cannot help but interpret them as overly optimistic since many economies struggle to take off again even in mid-2020 (Strauss, 2020). Under a baseline scenario, output levels in advanced economies are projected to reach pre-crisis output levels only after 2022 (FED, 2020; Lane, 2020). As a result, global copper demand in 2020 is projected to contract by 18 percent, suggesting that copper prices have yet to face a reckoning after their mid-2020 sprint (Smith, 2020). The partially restored market confidence since April 2020 and resuscitated investment in emerging economies are unlikely to offset protracted recoveries in the Global North. In the absence of supply adjustments, a market-sustained return to pre-crisis commodity prices is therefore unlikely in the short-term. Even in the event of demand surges born in the real economy, surplus production in early 2020 replenished existing stockpiles which will dampen upward pressures on prices (Emerald, 2020; Hoskyns, 2020).

The currently elevated price levels likely fail to account for exceptional uncertainty. Copper prices hinge on extraordinary public infrastructure investments in electric grids, but constrained fiscal space and rising debt in many countries could mean that fiscal stimuli are smaller than expected (The Economist, 2020b). Analysts largely maintained their conservative longer-term price projections for the copper market, implying that market fundamentals had not changed (Taylor, 2020). The Australian Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources expects a modest 2 percent growth of copper prices in 2021, fueled by sizeable fiscal stimuli and infrastructure investments in China and other emerging economies that substitute for meager private sector demand. A mild uptick in 2021 will be driven by the recovery of the Chinese economy, which is projected to return to its GDP growth rate of 2011 at 9.2 percent.

Despite the deterioration of Chile’s terms of trade, the country’s current account deficit is projected to narrow from -3.9 percent of GDP in 2019 to -0.9 in 2020 (IMF, 2020c, p.22). This is a pattern empirically familiar from the financial crisis when imports shrank more than exports. In 2020, loan provision by the financial sector will contract and decrease leveraged demand for imports, while the mining sector will likely be able to limit the volume loss to 5.5 percent (Reyes, 2020). Even during the height of infections, mines continued to operate close to pre-crisis levels even with reduced staff. Therefore, of the expected global supply contraction of 141,000 tons, Chile is forecast to only bear 7 percent (10,000 tons). This would spare exporters and the wider economy from a destructive effect accruing from a decrease in export volume. Moreover, the floating exchange rate—the peso traded at low levels throughout 2020 and reached a historic low of 0.00116 dollars in April—will allow Chilean exporters to remain price-competitive vis-à-vis Congolese, Russian, and Australian producers.

Shrinking proceeds from mining exports will reduce tax collection by approximately 5 percent of GDP. In fact, 31 percent of Chile’s total government revenues and 42 percent of indirect taxes depend on the mining industry (Chisari, 2019, p.7). Especially the state-owned enterprise Codelco contributes to the budget through a 40 percent surcharge on top of the corporate tax rate and a 10 percent mining royalty (AFDB, 2015, p.10). Despite their comeback since March, average copper prices in 2020 remain substantially below their levels in 2018 and 2019 with a negative future outlook. Lower prices will squeeze the margins of copper exporters, push less-profitable mines out of the market, and threaten exploration projects in development. These factors will substantially decrease profitability and tax collection in the mining sector, which underlines the need for the Chilean government to deepen and diversify government revenue. In response to the pandemic, the Chilean government plans to offer tax deferments of approximately 2.1 percent GDP, further pushing down revenue (Ministerio de Hacienda. 2020b). When copper prices fell during the financial crisis by more than 60 percent, Chile’s tax revenue decreased by approximately 5 percent of GDP. While the COVID-19 pandemic has not caused a comparable price devaluation, copper prices will stay low for longer and will likely cause a comparable effect on the budget.

The imminent recession threatens to undo successes in poverty reduction. Government measures taken in mid-March protect employment, suspend tax payments, bolster unemployment insurance, and provide cash transfers for the most vulnerable. They also include social protection programs which ensure food delivery to 1.6 million students, a one-time payment of 50,000 pesos (ca. US$59) to two million people without formal work, and paid leave for Chileans without access to remote work (Gentilini, 2020; TK, 2020). These efforts will most likely be successful in easing the immediate plight of the vulnerable, but the 2020 recession will increase poverty regardless of the measures taken, as past successes in poverty eradication largely hinged on income effects from economic growth (Figure 11). Containment measures like curfews disproportionally hurt the poor, who depend on daily work for their income, and the primary sector, which employs many low-payed laborers, will face a strong reduction in profits in 2020. Starting in 2021, the government will face strong pressures to decrease fiscal spending, threatening the continuity of pro-poor policies.

References

AFDB (2015). Chile’s Fiscal Policy and Mining Revenue, A Case Study. African Natural Resources Center & African Development Bank. Retrieved from: https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/anrc/CHILE_CASESTUDY_ENG__HR_PAGES.pdf

Barrera, P. (April 1st, 2020). COVID-19: Copper Mines Impacted by Coronavirus Measures. Copper Investing News. Retrieved from: https://investingnews.com/daily/resource-investing/base-metals-investing/copper-investing/covid-19-copper-mines-coronavirus/

Castiglioni, R. (2020). La Batalla de Chile contra el COVID-19. Agenda Pública (25 March 2020). Retrieved from: http://agendapublica.elpais.com/la-batalla-de-chile-contra-el-covid-19/

Chisari, O. O., Mastronardi, L. J., & Romero, C. A. (2019). Precios de commodities y parámetros críticos para el desempeño macroeconómico: un análisis de equilibrio general computado para Argentina, Brasil y Chile. Estudios económicos, 36(72), 5-26.

De Gregorio, J., & Labbé, F. (2011). Copper, the real exchange rate and macroeconomic fluctuations in Chile. Beyond the Curse: Policies to Harness the Power of Natural Resources, 203-33.

DIPRES (2019). Reporte Activos consolidados del Tesoro Publico. Dirección de Presopuestos Gobierno de Chile. Retrieved from: http://www.dipres.gob.cl/598/articles-196439_doc_pdf.pdf

Emerald Insights (2020). COVID-19 will crimp copper demand, dampening the price. Expert Briefing. Retrieved from: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/OXAN-DB251923/full/html

Eurostat (2020). Impact of COVID-19 Crisis on Industrial Production. Eurostat. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Impact_of_Covid-19_crisis_on_industrial_production

FED (2020). June 10, 2020: FOMC Projections materials. Federal Open Market Committee (10 June 2020). Retrieved from: https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcprojtabl20200610.htm

FT (2020). Coronavirus tracked: the latest figures as countries reopen . The Financial Times (03 August 2020). Retrieved from: https://www.ft.com/content/a2901ce8-5eb7-4633-b89c-cbdf5b386938

Gentilini, U., Almenfi, M., & Orton, I. (2020). Social Protection and Jobs Responses to COVID-19: A Real-Time Review of Country Measures. Live Document. World Bank, Washington, DC. Retrieved from: http://www.ugogentilini.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Country-SP-COVID-responses_April10.pdf

Gomez, M. (December 2, 2019). Chile tendrá en 2020 el mayor déficit fiscal de los últimos 30 años. Pauta. Retrieved from: https://www.pauta.cl/economia/en-2020-chile-tendra-el-mayor-deficit-fiscal-de-los-ultimos-30-anos

Harris, P. (2020). Chile maintains copper exports. Mining Journal (07 July 2020) Retrieved from: https://www.mining-journal.com/copper-news/news/1390423/chile-maintains-copper-production-and-exports

Home, A. (2020). Column: Funds buy into a copper rally fuelled by China and Chile. Reuters (14 July 2020). Retrieved from: https://uk.reuters.com/article/us-metals-copper-ahome/column-funds-buy-into-a-copper-rally-fuelled-by-china-and-chile-idUKKCN24F1M7

Hoskyns, T. (April 8th, 2020). Rising metals inventory could impact prices 'for next decade', says RBC. MiningJournal. Retrieved from: https://www.mining-journal.com/covid-19/news/1384553/rising-metals-inventory-could-impact-prices-for-next-decade-says-rbc

IIF (April 17th, 2020). Global Policy Responses – Developed Markets. Institute of International Finance. Retrieved from: https://www.iif.com/Portals/0/Files/Databases/COVID-19_responses.pdf?ver=2020-04-10-173749-083

IMF (2020a). Global Financial Stability Overview: Markets in the Time of COVID-19. International Monetary Fund (April 2020).

IMF (2020b). Policy Responses to Covid-19. International Monetary Fund (08 April 2020). Retrieved from: https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19#C

IMF (2020c). World Economic Outlook. International Monetary Fund (April 2020).

IMF (2020d). Request for an Arrangement under the Flexible Credit Line. IMF Country Report No. 20/183. International Monetary Fund (May 2020).

IMF Blogs (2020). COVID-19 Pandemic and Latin America and the Caribbean: Time for Strong Policy Actions. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from: https://blogs.imf.org/2020/03/19/covid-19-pandemic-and-latin-america-and-the-caribbean-time-for-strong-policy-actions/

International Construction (April 16th, 2020). Construction and Covid-19: rolling news update. KHL. Retrieved from: https://www.khl.com/international-construction/construction-and-covid-19-rolling-news-update/142849.article

Jiménez Molina, A., Duarte, F., & Rojas, G. (2020). Sindemia, la triple crisis social, sanitaria y económica; y su efecto en la salud mental. CIPER (20 June 2020). Retrieved from: https://ciperchile.cl/2020/06/20/sindemia-la-triple-crisis-social-sanitaria-y-economica-y-su-efecto-en-la-salud-mental/

Lane, P. R. (2020). The macroeconomic impact of the pandemic and the policy response. Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank (04 August 2020).

Medina, J. P., & Soto, C. (2007). Copper price, fiscal policy and business cycle in Chile. Banco Central de Chile.

Ministerio de Hacienda (February 2020a). Valor de Mercado. Gobierno de Chile. Retrieved from: https://www.hacienda.cl/fondos-soberanos/fondo-de-estabilizacion-economica-y/informacion-financiera/valor-de-mercado.html

Ministerio de Hacienda (March 19th, 2020b). Ministro de Hacienda: “Se trata de cifras inéditas, pero los momentos excepcionales, requieren medidas excepcionales”. Gobierno de Chile. Retrieved from: https://www.hacienda.cl/sala-de-prensa/noticias/destacadas/ministro-de-hacienda-presenta-medidas.html

Pollock, M. (April 16th, 2020). US construction declined 5% in March. KHL. Retrieved from: https://www.khl.com/international-construction/uk-construction-declined-5-in-march/143452.article

Prensa Presidencia (March 19th, 2020). Presidente presenta plan económico de emergencia por US$11.750 millones para proteger el empleo y a las pymes: “Necesitamos unidad”. Retrieved from: https://prensa.presidencia.cl/comunicado.aspx?id=148684

Regencia, T., Siddiqui, U., & Allahoum, R. (April 18th, 2020). Global coronavirus death toll crosses 150,000: Live updates. Al Jazeera. Retrieved from: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/coronavirus-deaths-35000-live-updates-200416234342434.html

Reuters (2020). Chilean copper giant Codelco records 3,215 cases of COVID-19; nine fatalities. Reuters (13 July 2020). Retrieved from: https://uk.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-chile-copper/chilean-copper-giant-codelco-records-3215-cases-of-covid-19-nine-fatalities-idUKKCN24E2VF

Reyes, V. (April 7th, 2020). Efecto Covid-19: Gobierno proyecta que Chile dejará de producir 10 mil toneladas de cobre. Biobiochile. Retrieved from: https://www.biobiochile.cl/noticias/economia/actualidad-economica/2020/04/07/efecto-covid-19-gobierno-proyecta-que-chile-dejara-de-producir-10-mil-toneladas-de-cobre.shtml

Sawhney, K. (April 17, 2020). Near Term Eye on Copper Prices: Commodity Outlook By 2025. Kalkine Media. Retrieved from: https://kalkinemedia.com/au/blog/near-term-eye-on-copper-prices-commodity-outlook-by-2025

Schwartzel, E., Sider, A., & Haddon, H. (April 13th, 2020). The Coronavirus Economic Reopening Will Be Fragile, Partial and Slow. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from: https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-coronavirus-economic-reopening-will-be-fragile-partial-and-slow-11586800447

Smith, E. (2020). Bank of America ups copper forecast as red metal rises for a second straight month. CNBC (01 June 2020). Retrieved from: https://www.cnbc.com/2020/06/01/bank-of-america-ups-copper-forecast-as-red-metal-rises-for-second-month.html

Strauss, D. (2020). Bank of England warns of slow recovery for UK economy. The Financial Times (06 August 2020).

USGS (2020). Copper Statistics and Information. Retrieved from: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/nmic/copper-statistics-and-information

Taylor, C. (2020). Copper prices could see a ‘supercharged recovery’ this year — but analysts are still cautious long term. CNBC (06 July 2020). Retrieved from: https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/06/copper-could-see-a-supercharged-recovery-but-analysts-are-cautious.html

The Economist (2020a). Why has China’s stimulus been so stingy?. Finance and Economics, The Economist (16 April 2020). Retrieved from: https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2020/04/16/why-has-chinas-stimulus-been-so-stingy

The Economist (2020b). Unusually, copper and gold prices are rising in tandem. Finance And Economics, The Economist (23 July 2020). Retrieved from: https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2020/07/23/unusually-copper-and-gold-prices-are-rising-in-tandem

TK (March 27th, 2020). Bono Covid-19: monto y cuándo se paga la ayuda por coronavirus. Tikitakas. Retrieved from: https://chile.as.com/chile/2020/03/24/tikitakas/1585055113_805931.html

Toledo, M. (April 16th, 2020). FMI destaca respuesta fiscal del Chile y del Banco Central ante Coronavirus. Diario Financiario. Retrieved from: https://www.df.cl/noticias/internacional/economia/fmi-destaca-respuesta-fiscal-de-chile-y-del-banco-central-ante-coronavirus/2020-04-16/145224.html

Trejo, C. (April 15th, 2020). Las medidas que frenan el coronavirus y la producción de cobre en Chile. Sputnik Mundo. Retrieved from: https://mundo.sputniknews.com/america-latina/202004151091127072-las-medidas-que-frenan-el-coronavirus-y-la-produccion-de-cobre-en-chile/

Vallejos, L. (2020). Estudio revela que movilidad en comunas de bajos ingresos de la RM se redujo sólo entre un 15% y 25% en cuarentena. Emol (29 May 2020). Retrieved from: https://www.emol.com/noticias/Nacional/2020/05/29/987542/Estudio-movilidad-RM-comunas-ingresos.html

Fuente: Emol.com - https://www.emol.com/noticias/Nacional/2020/05/29/987542/Estudio-movilidad-RM-comunas-ingresos.html

Vergara Perucich, F., Encinas, F., Aguirre Núñez, C., Truffello, R., Correa, J., & Ladrón de Guevara, F. (2020). Ciudad y COVID-19: Desigualdad socio espacial y vulnerabilidad. CIPER (25 March 2020). Retrieved from: https://ciperchile.cl/2020/03/25/ciudad-y-covid-19-desigualdad-socio-espacial-y-vulnerabilidad/

World Bank (April 2020). The Economy in the Time of Covid-19. Semiannual Report of the Latin America and Caribbean Region.

PHOTO CREDIT: Free use image from Canva Pro.