BY YUE JIANG (JOY)

Yue Jiang (Joy) is a first year Energy, Resources, and Environment student at Johns Hopkins SAIS.

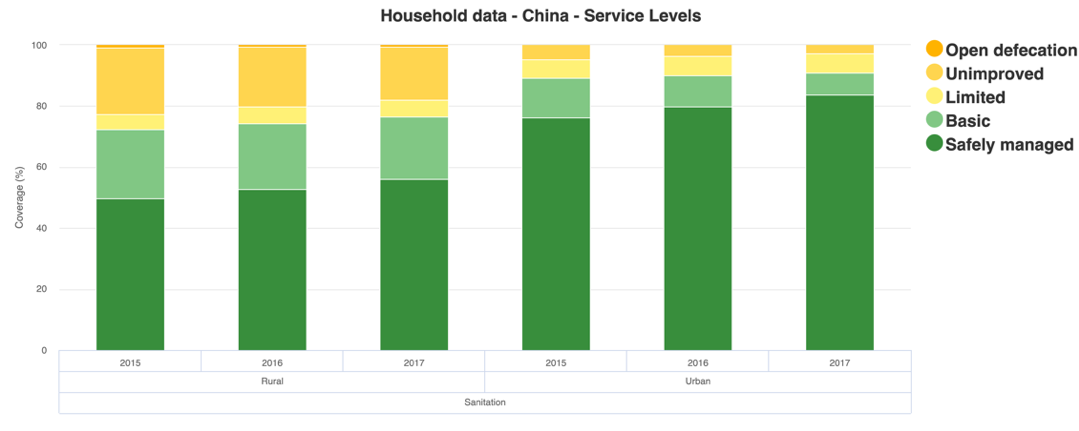

The association of toilets in China can be one of smell, bugs, small size, and no toilet paper or doors. There are also substantial rural-urban disparities. The National Bureau of Statistics (2018) notes that 340 million people living in rural areas in China have never used a flushing toilet. The number in the urban regions is half this figure, although the urban population is 20 percent higher than the rural population.

Figure 1: Chinese sanitation condition in rural and urban areas from 2015 to 2017. Source: JMP

In 2015, Chinese President Xi launched a “Toilet Revolution” campaign to improve public sanitation conditions, especially in tourist destinations. The original goal was to boost tourism, but in 2017 it was expanded to include the upgrading of restrooms in rural regions. To build odor-free and modernized restrooms, the Chinese government laid down requirements and combined these with an awards system. Each province, city, town, and village has its quota of renovation or construction projects to be undertaken, and households can receivean RMB 200 reward on top of the full reimbursement of the renovation expense. All the toilets in tourist attractions are standardized by a national requirement: feces must be disposed of in a manner that produces no harm to the environment or individuals.

From 2015 to 2017, 71,000 toilets nationwide were renovated, which is higher than the published initial aim. Another 64,000 toilets (47,000 built and 17,000 renovated) are scheduled to be completed by 2021. In 2019, a total of 53,700 tourist toilets were built nationwide, and 123 percent of the 2019 target plan was achieved. Consequently, there are now significantly more Chinese people with access to clean, sanitary facilities.

So far, the policy has been considered a success since it has substantially improved both public and private toilets in the country and probably led to positive medical, social, and economic impacts. Eliminating epidemics and increasing social awareness of sanitation are especially critical in this coronavirus-threatened world. One of the factors of success is the continuity of this policy. China has a long experience in national “toilet-related” campaigns since the establishment of the country, and the government has been subsidizing toilets construction and renovations, despite several failures in the early years mainly caused by a low household income level.

In 2016, the importance of the issue was emphasized by the Central Committee of the Communist Party. As a one-party state, this policy can be smoothly implemented as it has been added to several national-level strategies, such as Health China 2030 Program. Consequently, this policy has been pursued actively for five years and is expected to continue. The concentration of power in the President Xi's hands favors policy implementation, and as a result, a campaign he favors easily becomes a priority across the political spectrum.

Sustainable financing is a huge plus for the “Toilet Revolution”. Almost all funding comes from the Ministry of Finance. In 2019, the central government budgeted RMB 7 billion for rural “toilet revolution” subsidies, enough for more than 10 million households. Recently, more private actors, especially technical innovation companies, have brought in investment.

Another factor is China’s unique central-local relationship. According to the government document, this policy should be conducted mainly by local governments with the central government' help. Local governments submitted the number of toilets built and renovated in a certain period, and the percentage of which passed the national standard of cleanness and accessibility. In this way, the central government ensures the proper use of subsidies.

In addition, local governments are responsible for following newly built laboratories maintenance and public education requirements. Central and local governments share the homogenous policy goal to improve sanitation through the top-down approach. Under the Chinese political system, local officials earn promotions based on their policy achievements. The motivation to align with the central government is, therefore, very high.

Consequently, some provincial governments even provide additional subsidies to ensure that the renovation or construction of toilets can be undertaken in poor households. For instance, Shandong province announced an RMB 900 subsidy per household for this project, more than four times the central government provides. The ambition to get recognition from the central government could result in “formalism,” whereby an emphasis on numbers or outcomes outweighs the needs of local populations. For example, many luxurious toilets whose marginal costs are pretty high have been built. Although the drawback is not significant for now, the loss of money and potential fraud can, in the long run, harm those in need of investment. With a stricter monitoring system and punishment of responsible officials, the situation can be improved.

Figure 2: A fenced luxurious toilet in a public park in the Guizhou province. Source: KPBS 2018

In summary, the “Toilet Revolution” in China has been a successful model for China. However, the continuity of policy and homogeneity between central and local governments are difficult to copy because they are closely linked to China’s centralized political system.

PHOTO CREDIT: Free use image from Canva Pro.